Posted on October 6, 2025

setting the stage for chandler and nabokov

when a raymond chandler postscript short enough to almost go unnoticed had me dredging the archives, I realized I might have to reopen a case from my past – one that may be impossible to solve…

in december 1944, raymond chandler wrote a letter to charles morton, the associate editor of the atlantic monthly. it’s a decent read, with plenty of insightfully pithy moments – in it, he mainly details his experiences as a screenwriter, bemoaning the state of hollywood as regards art and money. but at the end, nearly slipping past me, he signs off with a postscript that had me intrigued:

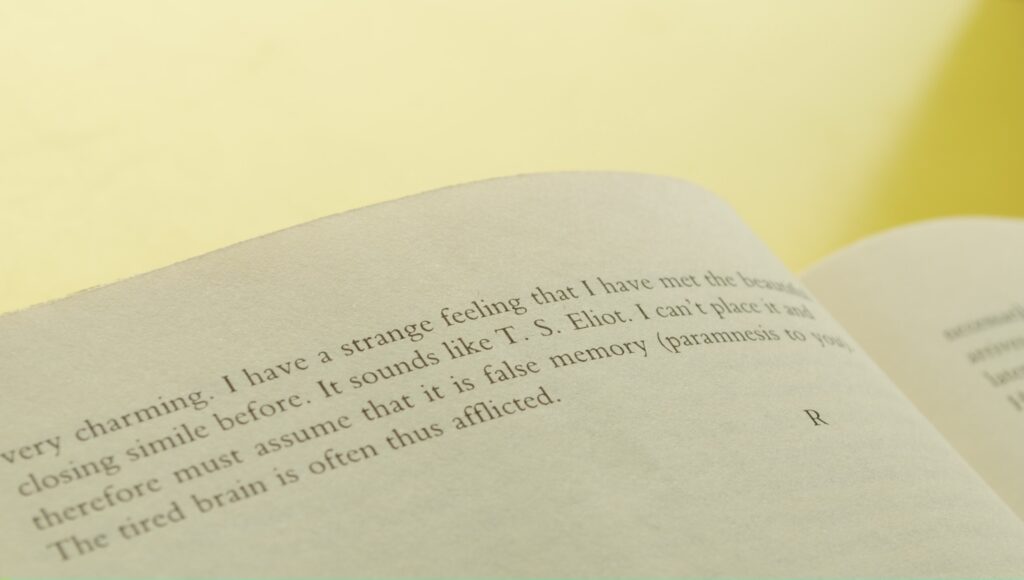

“P.S. I clean forgot to thank you for the proof of Nabokov’s fantasy. I have a novel by him somewhere. It is exquisitely composed and very charming. I have a strange feeling that I have met the beautiful closing simile before. It sounds like T. S. Eliot. I can’t place it and therefore must assume that it is false memory (paramnesis to you). The tired brain is often thus afflicted.”

the nabokov story in question, a then as-yet unpublished short story for the atlantic, was time and ebb, which would come out in the january 1945 edition. my interest was piqued – but, with a snag. nabokov had been a firm fixation of mine for many years, until just recently, when – for reasons probably too complicated to go into now – he was banished from my circle of friends (along with my bookshelves), and peremptorily packed off to go into storage. not to add undue drama to the recounting, but I did feel some hesitation in reopening the boxes (and some relatively fresh wounds) to get out his collected short stories… but with a clue like that, I couldn’t look away.

I found the story easily enough, but it wasn’t one that had particularly impressed me before – but, I couldn’t help wondering: aside from the story in question, what novel of nabokov’s would he have been referring to? and, was there a chance he meant the closing simile of the novel, rather than the story (as unlikely as that might be)?

so, despite my reservations, I dug back into the archives to try and answer those questions, grabbing the novels most likely to have been the culprits. looking into it, I guessed that the one he referred to was the real life of sebastian knight (1941), despite there being two other potential suspects – my reasoning was thus:

- 1937 – Despair (translated into english), most copies were destroyed by german bombings during WWII, and was only re-released in a new translation in 1965

- 1938 – Laughter in the Dark (translated into english) – a slightly complicated publication history, where it was first translated in 1936 as camera obscura but nabokov hated it so much that he retranslated (and republished) it in 1938 – a somewhat more likely candidate than the previous

- 1941 – The Real Life of Sebastian Knight (written in english)

my suspicion is that chandler would be likeliest to have a copy of sebastian knight (perhaps via the same means he received the short story – through an editor, publisher and/or friend), but I can’t swear to that being true. I would love to know more, but alas, there appears to be less fans of the sort that would archive his personal library as I would have expected. as such, just to be sure, I trawled through the ending sections of all three novels to see if they held any beautiful closing similes.

short answer: no, none of the three appear to end with similes at all. case closed, right? but, still, I found myself puzzling over those three endings. there was something else that they shared – a curious resonance between themselves, but also… with raymond chandler’s work, too.

each of these stories, in their own way, deals with death through the lens of (at times farcical) madness – despair, in an attempted ‘perfect’ murder plot wherein he fakes his own death, thinking he is the victim’s double (he is not); laughter in the dark with a blinded and cuckolded man attempting to murder his torturous mistress; and in sebastian knight, with an investigation conducted by the half-brother of the eponymous, now deceased, knight.

while seemingly disparate, these novels end with their narrators stepping back to reveal some level of falsity in the text by turning to metaphors from the theatre or cinema – not quite breaking the 4th wall, but in a sense acknowledging that they are ‘characters’ playing parts:

despair (1937)

(in this passage, the narrator is describing an attempt to escape from a police-surrounded hotel)

“How about opening the window and making a little speech… ‘Frenchmen! This is a rehearsal. Hold those policemen. A famous film actor will presently come running out of this house. He is an arch-criminal but he must escape. You are asked to prevent them from grabbing him. This is part of the plot. French crowd! I want you to make a free passage for him from door to car. Remove its driver! Start the motor! Hold those policemen, knock them down, sit on them – we pay them for it. This is a German company, so excuse my French. Les preneurs de vues, my technicians and armed advisers are already among you. Attention! I want a clean getaway. That’s all. Thank you.

I’m coming out now.”

laughter in the dark (1938)

“He sat on the floor with bowed head, then bent slowly forward and fell, like a big, soft doll, to one side.

Stage directions for last silent scene: door – wide open. Table – thrust away from it. Carpet – bulging up at table foot in a frozen wave. Chair – lying close by dead body of man in a purplish brown suit and felt slippers. Automatic pistol not visible. It is under him. Cabinet where the miniatures had been – empty. On the other (small) table, on which ages ago a porcelain ballet-dancer stood (later transferred to another room) lies a woman’s glove, black outside, white inside. By the striped sofa stands a smart suitcase, with a coloured label still adhering to it:

‘Rouginard, Hôtel Britannia’.

The door leading from the hall to the landing is wide open, too.”

the real life of sebastian knight (1941)

“Thus I am Sebastian Knight. I feel as if I were impersonating him on a lighted stage, with the people he knew coming and going – the dim figures of the few friends he had, the scholar, and the poet, and the painter, smoothly and noiselessly paying their graceful tribute …They move round Sebastian – round me who am acting Sebastian, and the old conjuror waits in the wings with his hidden rabbit; and Nina sits on a table in the brightest corner of the stage, with a wineglass of fuchsined water, under a painted palm. And then the masquerade draws to a close. The bald little prompter shuts his book, as the light fades gently. The end, the end. They all go back to their everyday life … but the hero remains, for, try as I may, I cannot get out of my part:

Sebastian’s mask clings to my face, the likeness will not be washed off. I am Sebastian, or Sebastian is I, or perhaps we both are someone whom neither of us knows.”

if you are at all familiar with chandler’s novels, you’ll know that this is a common conceit throughout – of the narrator or characters conversationally acknowledging that they are acting in some kind of construction, whether that be a book, play or film. some examples from the novels*:

the big sleep (1939):

“There’s no hurry. All this was arranged in advance, rehearsed to the last detail, timed to the split second. Just like a radio program. No hurry at all.”

the high window (1942):

“All right,” he said wearily. “Get on with it. I have a feeling you are going to be very brilliant. Remorseless flow of logic and intuition and all that rot. Just like a detective in a book.”

“Sure. Taking the evidence piece by piece, putting it all together in a neat pattern, sneaking in an odd bit I had on my hip here and there, analyzing the motives and characters and making them out to be quite different from what anybody — or I myself for that matter — thought them to be up to this golden moment — and finally making a sort of world-weary pounce on the least promising suspect.”

He lifted his eyes and almost smiled. “Who thereupon turns as pale as paper, froths at the mouth, and pulls a gun out of his right ear.”

I sat down near him and got a cigarette out. “That’s right. We ought to play it together sometime.”

the little sister (1949):

chapter 12

“I’m beginning to think you write your own dialogue,” I said. “I’ve been wondering just what was the matter with it.”

chapters 27, 28

“I-I-” She broke off and made a helpless gesture. “I can’t think of any lines tonight.”

“It’s the technicolor dialogue,” I said. “It freezes up on you.”

…

She dropped the gun to her side and for a moment she just stood staring at me. Then she tossed the gun down on the davenport.

“I guess I don’t like the script,” she said. “I don’t like the lines. It just isn’t me, if you know what I mean.”

chapter 33

“The play was over. I was sitting in the empty theater. The curtain was down and projected on it dimly I could see the action. But already some of the actors were getting vague and unreal.”

to me, there’s just something fantastical to imagine here, as a schism in the accepted chronology – twofold, of chandler reading a proof of a story before it was ‘officially’ published, and how the thematic and stylistic echoes between the two blur the strange demarcations that we impose between ‘literature’ and ‘pulp’. most wouldn’t describe nabokov as a mystery or crime author, despite quite a few of his books centering around murder and its machinations – and while chandler is one of a handful of hardboiled authors considered ‘elevated’ within the form, even he bemoaned the arbitrary divide and how it impacted himself and his peers.

someday I’d like to talk about all this in more depth (especially since, in investigating this case, I saw “literati” claiming Nabokov is “better at noir than Raymond Chandler”, a baseless assertion I have been puzzling over for days), but for now – the beautiful closing simile that started the case, and one that certainly rings true to the spirit of investigation:

time and ebb (1945)

(the narrator is describing their alternative future where airplanes are banned)

“Admirable monsters, great flying machines, they have gone, they have vanished like that flock of swans which passed with a mighty swish of multitudinous wings one spring night above Knights Lake in Maine, from the unknown into the unknown: swans of a species never determined by science, never seen before, never seen since and then nothing but a lone star remained in the sky, like an asterisk leading to an undiscoverable footnote.”

* chandler was known to, as he put it, ‘cannibalize’ his short stories into his novels, so there’s a lot of overlap between them – I would have to do a closer read to compare the specific lines in question, but the original publication dates when he proliferated these ideas may have originated earlier than the novels… or, may have been a later addition as he retooled the writing. until I can do that closer read, here’s the story-to-novel transubstantiation timeline for the works I quoted above:

- The Big Sleep (1939) —> “Killer in the Rain” (1935) and “The Curtain” (1936)

- The High Window (1942) —> none!

- The Little Sister (1949) —> “Bay City Blues” (1938)